The original ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) study, published in 1998, confirmed what physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, substance abuse counselors and school principals had long suspected: that abuse, neglect and trauma in early childhood have a lifelong impact on health and behavior. But the study surprised even its authors, Drs. Robert Anda and Vincent Felitti, in showing how many people—even among a mostly white, well-educated, medically insured cohort of California adults—were touched by adverse experiences.

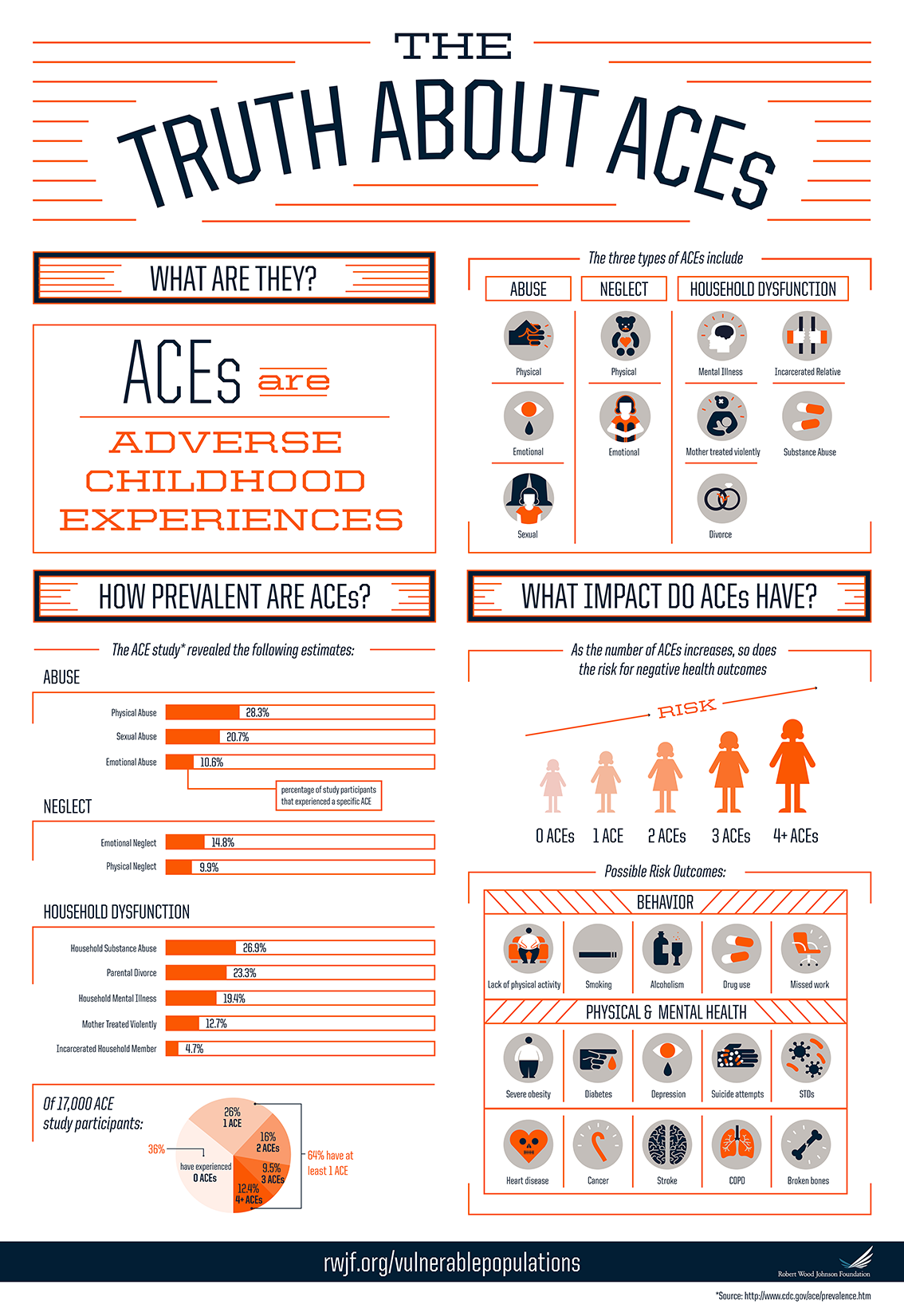

The study, of more than 17,000 members of Kaiser Permanente, which is one of the largest not-for-profit health plans, asked participants about family dysfunction (parental separation or divorce, growing up with a household member with a mental illness or substance abuse problem, witnessing domestic violence, or incarceration of a household member), emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and emotional and physical neglect.

The conclusion: ACEs were common. ACEs were highly interrelated; where there was one ACE in the life of a child, there tended to be others. And the effects of ACEs accumulated: the more ACEs a person had during childhood, the greater his or her risk for social, mental and physical health problems throughout the lifespan.

High ACE scores were correlated with a host of medical and social ills—not just heart disease and diabetes, but substance abuse, intimate partner violence, suicide attempts and adolescent pregnancy, divorce, financial problems, and difficulty performing in the workplace. Research has shown how that happens: childhood adversity can affect the developing brain, leading to social, emotional and cognitive impairments. That, in turn, can lead to risky behaviors such as smoking, substance abuse, overeating, early and unprotected sexual activity.

Those behaviors set the stage for dysregulation, disease, disability and early death.

Since the original study was published, states and localities have begun to collect their own ACE data. Those surveys drummed home the same conclusion: abuse, neglect and trauma shape the way we learn, play and grow. Stress can literally make people sick. What happens at home in the early years—and into adolescence and early adulthood—affects health across the lifespan.

Data collected as part of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) in Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Tennessee and Washington showed that ACEs were just as common in those places as they were among the original Kaiser sample: nearly 60% of 26,000 adults had one or more ACE, and 8.7% had five or more.

State data also showed that ACEs hit some groups harder than others. People with the least education also were the most likely to report five or more ACEs. Those lacking a high school diploma had greater prevalence of physical abuse, an incarcerated family member, a parent with a substance abuse problem and parental separation or divorce.

But these studies were conducted with adults, who were recalling childhood experiences that happened ten, twenty or even seventy years earlier. What about the impact of ACEs on children growing up now?

The 2011-12 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), which includes many of the areas covered in the Kaiser study, but excludes physical, sexual, emotional abuse and neglect, answered that question: it showed that ACEs were widespread among the current generation of kids. Nearly 48% of United States children — that’s 34,825,978 kids aged zero to 17 — had one or more ACE.

These surveys differed a little from the original ACE questionnaire posed to Kaiser adults; they included witnessing neighborhood violence and suffering racial/ethnic discrimination as sources of adversity.

The NSCH data showed that poor children, children of color and children with either public health insurance or no insurance were especially at risk. In a chicken-and-egg conundrum, children with chronic health conditions experienced more ACEs, and having more ACEs made children vulnerable to such health problems

Local data, collected by individual clinics and in some urban areas, have shown even more alarming rates of ACEs:

-

The 11th Street Family Health Services Center surveyed patients and found 49% had 4 or more ACEs At the Oklahoma University-Tulsa School of Community Medicine clinic, 30% of patients reported five or more ACEs

- At the Bayview Child Health Center in San Francisco, 67.2% of patients had one or more ACE, with 12% reporting four or more ACEs

- Practitioners at Philadelphia’s 11th Street Family Health Services found that 49% of their patients had four or more ACEs

In Philadelphia, members of the ACE Task Force—a group that includes doctors, behavioral health specialists, social service providers and researchers—wondered if living in an urban area might bring particular stresses not covered in the original ACE study, which focused primarily on household adversities. Their Philadelphia ACE Study, conducted in 2013, asked 1,784 adult participants additional questions related to community-level adversities.

More than half of participants in the Philadelphia ACE Study experienced ACEs, with similarly high rates of household and community level adversities. These data, in parallel with NCSH findings, suggest that the actual rates of adversity experienced by children in our communities may be underestimated when based on household-level adversities alone.

The ACE numbers tell a compelling story: ACEs are common in children and adults. They are corrosive to individuals, families and communities. They cost money in emergency room care, missed days of work, substance abuse treatment and incarceration.

But they are not a life sentence. As localities and states focus on treating and preventing ACEs, they are learning some of the good news: the behaviors, skills and interventions that help people to recover from trauma also nurture the next generation.

We are beginning to learn what works. Data from the NSCH shows that children who receive health care within a medical home model—a team-based approach to providing comprehensive health services—are more likely to have positive health outcomes, even among children already affected by ACEs.

Other NSCH data shows that children who are resilient—able to stay calm and in control when faced with challenges—are less likely to miss days of school or to repeat a grade, even when they have two or more ACEs. And resilience is not just a gift of nature; it’s a skill that kids and adults can learn to help buffer and heal the damage caused by early adversity.

Robert Anda, co-principal investigator of the original ACE Study, believes in the power of individuals to repair brokenness in themselves and in others. “Our job in doing this work is to help people find meaning in what they’ve experienced,” he said at the National Summit on ACEs in Philadelphia in 2013, “so they can take responsibility in changing their own lives, in healing themselves, their families and people around them, in interrupting the intergenerational transmission of toxic stress.”

A fascinating and inspiring presentation by Dr. Rob Anda at the National Summit on ACEs in Philadelphia: “ACES in Society – Where the Sciences Collide”

Reflection Questions:

- What was the most compelling thing you learned from reading this section?

- How could it apply to your work?

- With whom do you want to share this new understanding?